As implied by the name, advanced review methodologies grew out of the more traditional literature review. Over the years, it became clear that for certain disciplines and certain research topics, the reliability and credibility of the findings of a review article required a more scientific approach to the methodology (Chalmers et al., 2002). While more structure was necessary at all stages, the one that stands out most for literature-based reviews is, naturally, how one finds the literature they intend to review.

Systematic and transparent searches are essential to advanced reviews, but the strategies employed can aid anyone hoping to conduct a stronger and more structured search. In this blog post, I’d like to share the way I’ve come to think about searching.

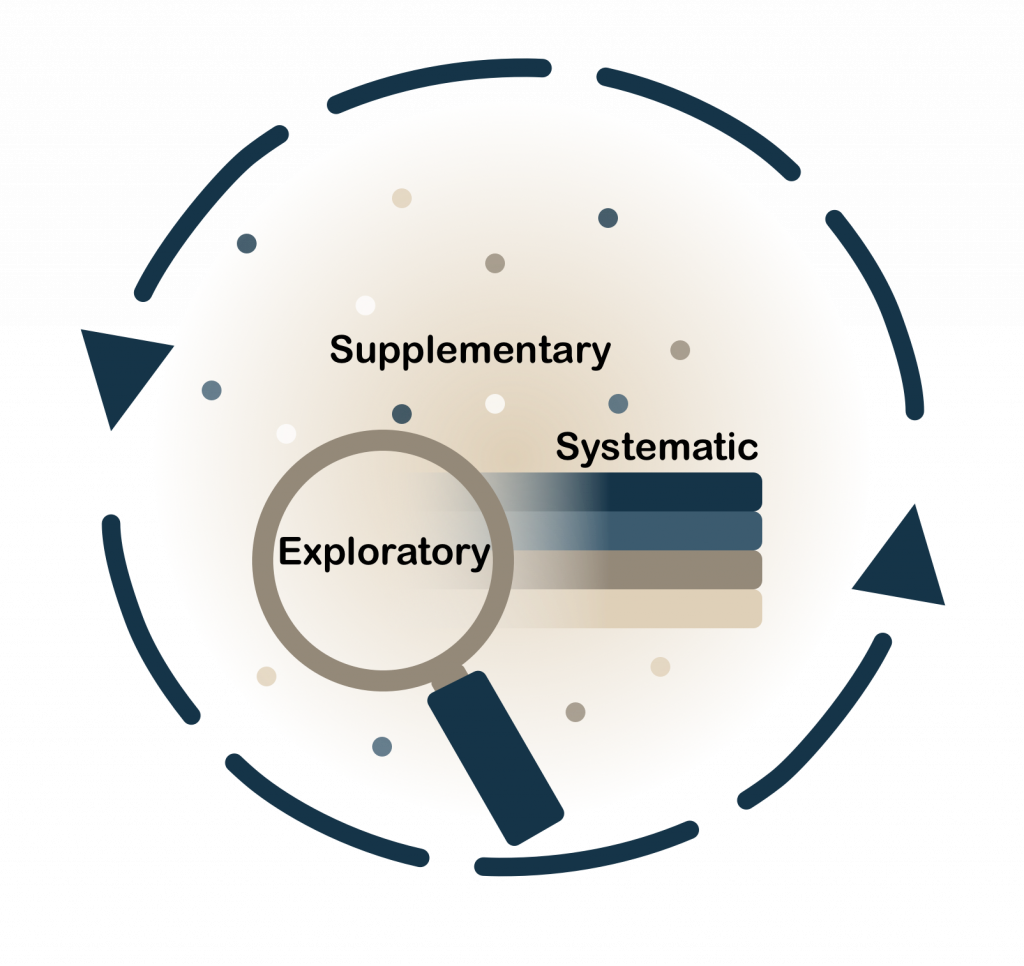

I’ve found it helpful to split the search process into three overlapping, but distinct phases:

- Exploratory

- Systematic

- Supplementary

Exploratory Searching

Exploratory searching is unstructured and iterative. You are literally exploring what’s out there. You learn as you go and there is no right or wrong way to go about it. Go to the databases or search engines you are most comfortable with and start entering key words you think are relevant for your topic. Examine the results. Are you getting any results at all? Are the articles relevant? Are the authors using different vocabulary than you used in your search? Are there papers you want to include in the background section of your manuscript that you can then build on?

Take what you’ve learned and expand your key words, and maybe expand where you are searching based on what you find. Begin to build a structured search strategy. This is how I develop the search strategy that I report in the protocol for my systematic or scoping review. For those types of projects, you’ll want to be sure you have the strategy completely written prior to the next phase.

In this phase you are doing a number of very important things:

- getting an idea if there’s enough literature to conduct the type of review you plan to conduct

- focusing and refining your research question into something you will be able to answer with the existing literature

- identifying exemplar articles you want to ensure get captured in your systematic search

- learning key terminology to help build your search strategy

- identifying related advanced reviews

- identifying databases and other information sources you want to be sure to search more thoroughly

- identifying key dates, trends, policies, etc. that might inform your research question, search strategy, and eligibility criteria

- identifying key journals and authors you may want to target for supplementary searching

- identifying index terms and subject headings for the relevant databases

- testing and building your search strategy.

Exploratory searching can take a long time, but don’t get discouraged. Spending more time up front ultimately saves you time later in the review process and makes your review that much better.

Systematic Searching

Systematic searching is the implementation of the search strategy that you built during exploratory searching. This is the search you will report in the methods section of your paper. For systematic reviews, be sure to document the date(s) you ran these searches.

The systematic search for all advanced reviews should be consistent across databases, but will need to be translated based on the syntax each database uses. You will also need to conduct the search individually for each database, noting the total number of results returned by each. These numbers should appear in a flow diagram in your methods section.

During this phase, you are only searching the academic databases which allow for systematic searches. Likely, the gray literature you find during this phase will be minimal. For an example of a systematic search translated for multiple databases, take a look at the search strategy for one of my published reviews (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VEQMJ).

Supplementary Searching

Supplementary searching is the nonlinear phase where you find and collect anything you want to include that may not be captured in your systematic search. You can begin this during exploratory searching if you find gray literature that looks relevant for your review. Hopefully during exploratory searching, you’ve also identified key journals and authors to hand search during this phase.

Your systematic search will provide you with more of those as well as reference lists to search. I recommend at minimum searching the reference lists of any articles that meet your eligibility criteria. You can also use Scopus, Web of Science, or Google Scholar to identify papers that have cited those. This is known as citation chasing, or forward and backward citation searching.

You may want to contact researchers who are experts in the field and see if they have any unpublished work or additional papers. Search government and nonprofit websites that may publish reports related to your topic.

This is also where I advocate for searching in Google Scholar. While Google Scholar is valuable as a search tool, it is not a database (it’s a search engine) and cannot be searched systematically due to the way Google’s algorithm functions. It also can’t handle the complex search strategies that advanced reviews often require and does not take quality into account in the results it provides, so you are more likely to come across junk science than you would be in the databases. However, it is still a great tool for ensuring that you haven’t missed anything important and highly cited in your research area.

For more on these search phases, you can check out the search page on my Scoping Reviews research guide.

References

Chalmers, I., Hedges, L. V., & Cooper, H. (2002). A Brief History of Research Synthesis. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 25(1), 12–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278702025001003