Editor’s note: This is a guest post written by E.M. Durham.

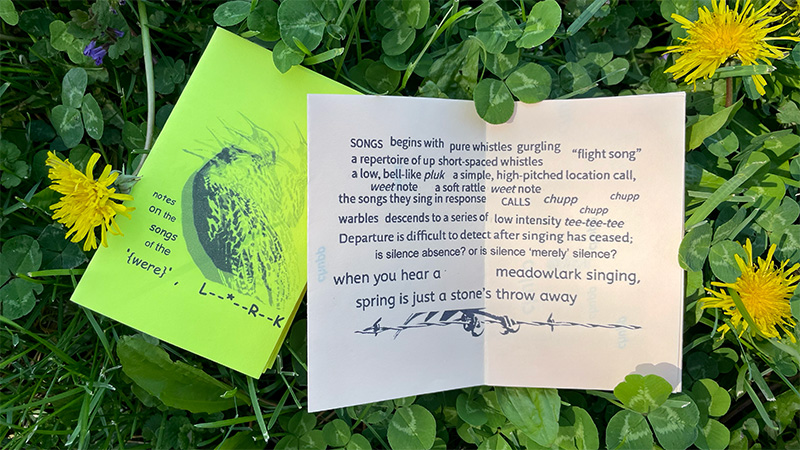

Spring arrived while I was thinking about and writing this post. Sweet lilacs bloomed flagrantly under the radiant sun as juicy dandelions popped up in crowds. Seasonal cues conjure memories of last year when I was deeply engaged in a project I loved. Research that led me down an unexpected path, influencing my future direction and approach.

I’m embarrassed to admit I’m now struggling through a semester-long research paper on topics I’m highly interested in but feel trapped by. I know I’m not the only one who’s faced this. My peers have shared similar challenges, whether feeling lost trying to form a research question or stuck after getting too far along to make significant changes. Do these frustrations seem familiar? If you’re an early-career researcher or new to advanced research, chances are you can relate.

I understand how I reached this point. A mix of circumstances resulted in a challenging, stressful semester. Pausing to reassess or change course can feel risky under pressure, but it’s often when it’s most beneficial. Had I done so, I might have applied the lessons I learned from my successes last spring and avoided my current dilemma.

Sitting with a consequence often makes me more receptive to learning, but time and focus may pass before a need arises to apply this lesson again. I risk continuing a regretful pattern if I don’t root this learning now, which brings me back to this post. I hope that sharing this reflection and introducing a research approach that I’ve found valuable might help you, too.

Introducing Exploratory “Research Before the Research”

Get to know your question with a flexible, low-stakes approach that encourages using any method to investigate a topic: exploratory “research before the research” [See also: Pre-Study, Informal Exploratory Study (Swedberg, 2020)]. Rather than produce a publication, the goals are to uncover insights, generate ideas, or refine a research question. In a recent conversation, Elle Covington likened the concept to the “research before the research” phase of forming a question. However, emphasis on “exploratory” demonstrates a useful distinction here.

Swedberg defines and proposes the Informal Exploratory Study in The Production of Knowledge and argues that graduate students should use the method before proposing a dissertation or thesis (pp. 32, 27–38 ). Exploratory “research before the research” may be beneficial when deciding on a topic for a research assignment, as your research agenda is shifting directions or entering unfamiliar ground, or simply when you are feeling stuck or uninspired.

How might one go about this type of research?

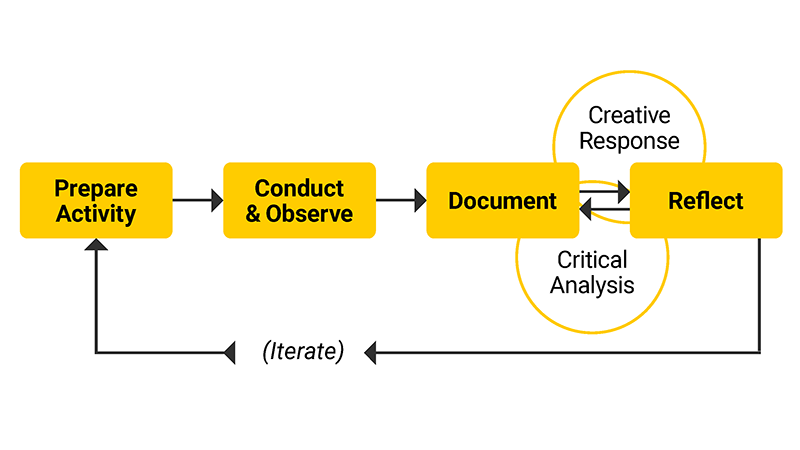

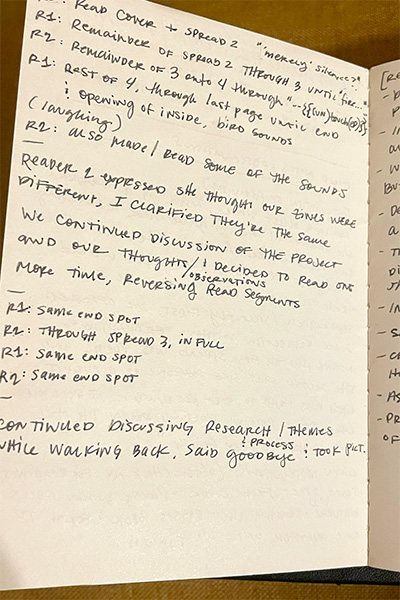

- Set clear parameters for your study. Identify a beginning, an end, and a measure like time or task count. These can be adjusted, but having them from the outset will provide a structure to guide and contain your process. I aligned my study with the course schedule and assignment, deciding on four weeks and observation activities.

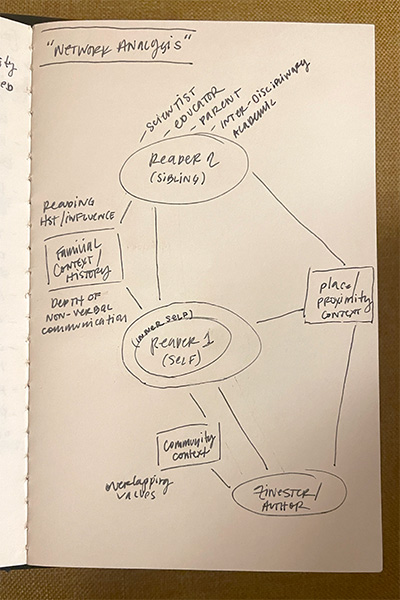

- Create conditions to observe your topic through different lenses. Examine your topic from a distinctly different discipline. Change up your research environment. Apply your personal interests and activities to your topic or vice versa.

- Employ non-traditional thinking approaches. Reflect on and respond to your observations using lateral, divergent, or creative thinking techniques, such as free-form mapping (mind, cognitive, concept, etc.), random association, drawing, creative writing, improv, and more.

- Review the literature. Designate times throughout your study for exploratory searching and revisiting your sources (which, hopefully, you are managing with a tool like Zotero!).

- Document with dedication. Take notes, organize reflections, maintain lists of keywords, and record processes. This turns casual curiosity toward intentional inquiry. Documentation is essential at all stages of this endeavor and will become a vital resource or provide you with the groundwork for your future research.

The value of this approach lies in how it liberates research from a linear, prescriptive, disciplined procedure. It opens up possibilities to weave the act of inquiry with personal interests, pastimes, or settings that already bring me enjoyment, awe, or meaning. In my experience, these are conditions that have led to my falling in love, instead of stumbling in contempt, with my research question

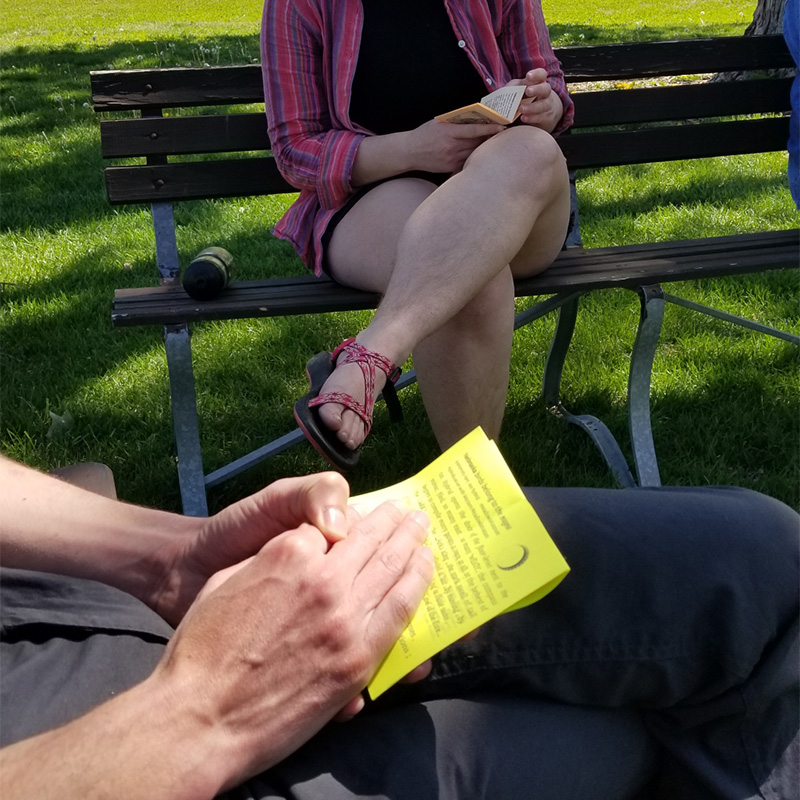

Are you planning a hike this summer? What would it look like to ‘study’ your topic while backpacking?

Are you a prolific dreamer with a dream journal? What insights may you gain by interpreting dreams with random associations to your topic?

Have you been deep in databases for months and miss your friends? How could sharing time with them become a ‘research moment’?

Reference:

Swedberg, R. (2020). “Exploratory research.” In C. Elman, J. Gerring, & J. Mahoney (Eds.), The Production of Knowledge: Enhancing Progress in Social Science (pp. 17–41). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author/Editor note:

At the time this was written, E.M. Durham was conducting a practicum at UNL Libraries’ Research Partnerships. Under the supervision of Scout Calvert, Durham assisted with data services and contributed to Research Partnerships’ efforts throughout the semester. Durham was completing a Master of Arts in Library Information Science at the University of Iowa and previously earned a Graduate Certificate in Digital Humanities from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.